Synthesis strategy and microstructure analysis

We previously demonstrated that piezoelectric polymer membranes based on single metal atoms are effective by anchoring isolated calcium (Ca) atoms onto nitrogen-doped carbon and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) composites [12]. Drawing on this prior research, we designed and improved the process to synthesize CaCN.

ZIF-8 coated Ca (Ca/ZIF-8) was prepared via a hydrothermal method, followed by calcination to manufacture CaCN (Supplementary Fig. 1). Zinc nitrate hexahydrate, calcium chloride, and dimethylimidazole were used as raw materials, and synthesis was carried out using a hydrothermal method in methanol, followed by carbonization. Then, acid etching was performed to not only remove residual zinc and calcium to avoid secondary pollution but also to generate more mesopores on the original structure of MOF, promoting pollutant adsorption and generating more surface catalytic reaction active sites. Morphology studies displayed that the introduction of Ca did not affect the structure of ZIF. SEM images of ZIF-8 and Ca/ZIF-8 materials depicted similar regular dodecahedron morphology (Supplementary Fig. 2 A). The powder XRD spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 2B) confirmed that ZIF-8 and Ca/ZIF-8 had comparable crystal phases.

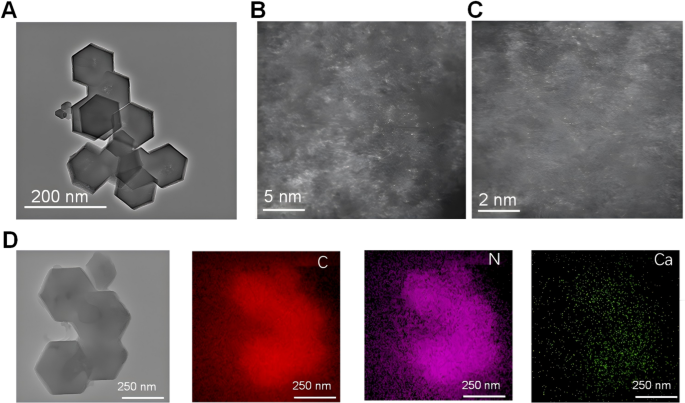

The morphological characteristics of CaCN were evaluated using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). As illustrated in Fig. 2A, the HR-TEM image of CaCN after high-temperature pyrolysis still showed a standard dodecahedron structure, indicating that high-temperature treatment did not affect the structure of the material and validating the high-temperature stability of CaCN materials. In order to clarify the existence form of Ca, aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM characterization of atomic resolution was conducted. As displayed in Figs. 2B and C, a large number of Ca atoms were dispersed in the carbon skeleton, further supporting the anchoring of a single Ca atom in the carbon framework by N and C atoms. Meanwhile, the energy-dispersive X-ray element mapping spectrum (EDS) image presented that the elements C, N, and Ca were evenly distributed in CaCN, as delineated in Fig. 2D. In addition, the existence of Ca and N was confirmed by electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS). Two peaks at approximately 350 eV and 400 eV were distributed on the characteristic Ca L edge and N K edge, respectively, which provided strong evidence that Ca exists as single atoms in CaCN (Supplementary Fig. 2 C).

Synthesis strategy and microstructure analysis. (A) HR-TEM of CaCN. (B, C) Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM image of CaCN with scale bars of 2 nm and 5 nm, showing that Ca in the carbon framework existing as single atom. (D) The HAADF-STEM image of the CaCN and the images of elemental mapping of C, N, and Ca in the CaCN

Chemical state and active site analysis

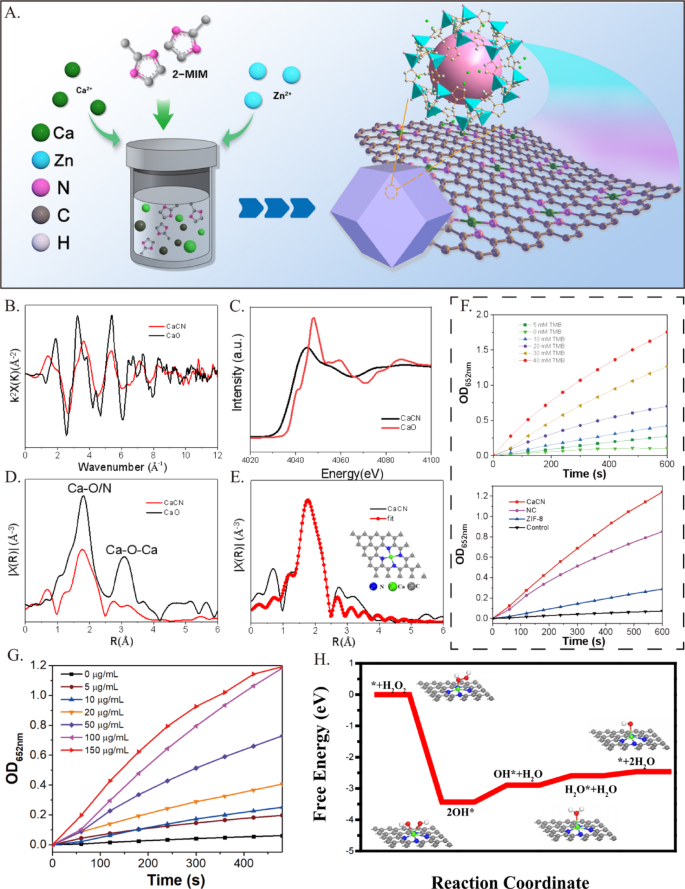

The electronic structure and local coordination environment of monatomic calcium were further determined through X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) to reveal the structure of active sites. Given that Ca is highly active in air, the Ca K-edge XANES spectrum of CaO was used as a calibration reference material. Figure 3B shows the K-space diagram of Ca K-edge EXAFS. It is emphasizing noting that the EXAFS curve of CaCN markedly differed from that of CaO. The CaCN uncorrected Ca K-edge Fourier transform (FT) – EXAFS curve showed that a main peak is at 1.9 Å, attributed to the Ca-N scattering path (Fig. 3C). As presented in Fig. 3D, the near-edge absorption spectrum of the CaCN catalyst closely matched the calcium-containing reference (CaO), suggesting that the Ca metal atom in CaCN was in a cationic state. Ca-O (1.8 Å) and Ca-O-Ca (3.1 Å) peaks were not detected in Ca/CN, corroborating the presence of only a single calcium atom in Ca/CN. Meanwhile, the quantitative local coordination parameters of the Ca atom were further examined via least square EXAFS fitting (Fig. 3E), uncovering a coordination number of 4 for the first shell and a Ca-N bond length of 2.27 Å. Furthermore, we previously demonstrated that the fitting results of EXAFS revealed that the R-factor value of the Ca-N4 structure was 0.0044, which is in good agreement with the characterization results of the sample, indicating that Ca-N4 is the active center of CaCN [12]. These results signified that the Ca atom coordinated with N atoms to form an active site. Taken together, the aforementioned results provided robust evidence for the successful synthesis of CaCN at the Ca – N4 site by combining atomic dispersed Ca with four N atoms.

To further investigate the catalytic performance of CaCN, the reaction kinetics and environmental responsiveness were evaluated under various conditions. The catalytic activity, monitored by the oxidation of TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) to produce a chromogenic product, demonstrated a clear dependence on catalyst concentration and substrate concentration (Fig. 3G), with CaCN exhibiting significantly higher activity compared to control materials (NC, ZIF-8, and blank) (Fig. 3F). Compared with natural horseradish peroxidase (HRP), CaCN exhibits a lower Km value and a higher apparent Vmax/Km ratio, which confers a relative advantage at sub-millimolar substrate concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 3 A). Temperature-dependent experiments revealed that the reaction rate increased with temperature, as evidenced by a more pronounced absorbance peak at 652 nm under 37 °C compared to 20 °C (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Furthermore, upon exposure to 1064 nm laser irradiation, the reaction was notably accelerated, attributed to laser-induced rapid temperature elevation, highlighting the potential of CaCN for photothermal-enhanced catalysis. The free energy profile (Fig. 3H) corroborated these observations, indicating that the Ca-N4 active center facilitates spontaneous reaction pathways with a significant reduction in energy barriers. Collectively, these results confirm that the unique single-atom Ca-N4 structure plays a pivotal role in the superior catalytic performance of CaCN under diverse reaction conditions.

Chemical State and Active Site Analysis. (A) The synthesis process of CaCN. Structural analysis of CaCN by X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) spectroscopy. (B) Fourier transform (FT) of the Ca K-edge extended XAFS (EXAFS) spectra of CaCN and CaO at k-space. (C) Ca K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure spectra of CaCN and CaO. (D) Fourier transform (FT) of the Ca K-edge extended XAFS (EXAFS) spectra of CaCN and CaO at R-space. (E) Corresponding EXAFS fitting curve of CaCN in R. Insets are the schematic model of Ca-N4. Light grey, blue, and green balls represent C, N, and Ca atoms, respectively. (F) Peroxidase-like activity of the Ca/CN-SAzyme at different Concentrations. (NC refers to the control sample prepared without Ca. Control refers to the condition without any added nanomaterials.). (G) Peroxidase-like activity of the Ca/CN-SAzyme at different Concentrations. (H) Proposed catalytic mechanism of Ca/CN-SAzyme

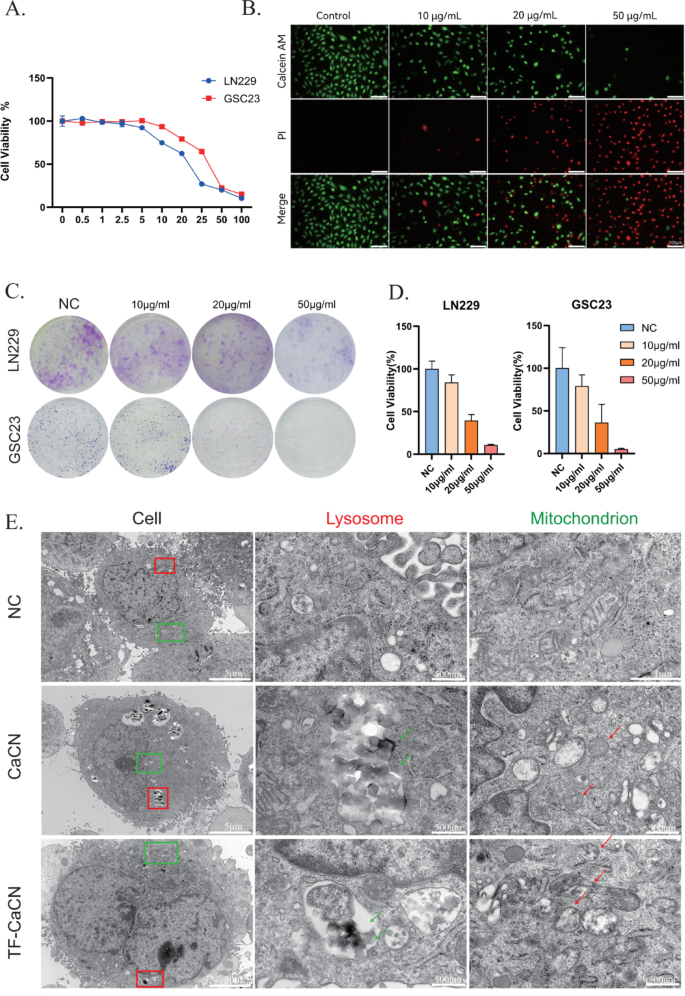

CaCN nanozymes induce glioma cell death

The anti-tumorigenic properties of CaCN were initially assessed at the cellular level. To examine the effects of different concentrations of CaCN on glioma cells, cell viability was determined using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay on LN229 and GSC23 cells treated with gradient concentrations of CaCN, respectively. Next, cell viability curves under each concentration of nanozyme treatment were plotted (Fig. 4A), and the IC50 of CaCN in LN229 and GSC23 cells was determined. Meanwhile, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of both ZIF-8 and CaCN, and the results showed that CaCN exhibited stronger cytotoxicity, which may be attributed to its higher catalytic activity (Fig. 3F). Specifically, the IC50 was 20.13 µg/ml in LN229 cells and 30.77 µg/ml in GSC23 cells. For subsequent experiments, we selected concentrations slightly above these values to ensure stable biological effects, namely 30 µg/ml for LN229 cells and 40 µg/ml for GSC23 cells. Therefore, for subsequent studies on TF-CaCN, we selected the same experimental concentration. We also compared the toxicity of TF-CaCN between normal astrocyte cells (NHA) and glioblastoma cells (LN229) using CCK8. The results showed that the IC50 value in the NHA cell line was much higher than that in the LN229 cell line (Supplementary Fig. 4B), indicating that the unique intracellular microenvironment of tumor cells is more favorable for catalysis by single-atom nanozymes. Because tumor cells generate more H2O2 than normal cells, we sought to investigate whether H2O2 affects the catalytic performance of CaCN inside cells. WB experiments showed that under treatment with only 25 µM H2O2 for 3 h, apoptosis markers were not altered. However, when cells were co-treated with CaCN and H2O2, the apoptosis markers were even higher than those observed with CaCN alone (Supplementary Fig. 4 C). This indicates that H2O2 enhances the catalytic effect of CaCN within cells. The inhibitory effect of CaCN on glioma cells was subsequently examined via live-dead fluorescence staining (Fig. 4B). The inhibitory effect of CaCN on the proliferative abilities of glioma cells was investigated using colony formation assay (Fig. 4C), demonstrating that different concentrations of CaCN exerted significant inhibitory effects on glioma cells (Fig. 4D). After treatment of glioma cells with CaCN at the IC50 concentration, visualization under TEM depicted that CaCN was intracellularly engulfed by glioma cells and predominantly localized in lysosomes and cytoplasm, whilst the area and perimeter of mitochondria in CaCN-treated cells was reduced. Besides, mitochondrial cristae almost disappeared compared to the mitochondria in the untreated cells (Fig. 4E). These results collectively suggested that CaCN treatment activated relevant death mechanisms and disrupted the normal morphology of mitochondria, eventually leading to glioma cell death.

CaCN nanozymes induce glioma cell death. A) Viability curves of LN229 and GSC23 cells treated with different concentrations of CaCN. B) Live and dead cell staining of LN229 cells with different concentrations of CaCN. C) Colony formation experiments of LN229 and GSC23 treated with different concentrations of CaCN. D) Percentage of cell viability for colony formation experiments obtained by imageJ counting. E) Transmission electron microscopy imaging of CaCN and TF-CaCN treated GSC23 cells before and after 12 h. (The red arrow indicates the lysosome engulfing the nanozyme, while the green arrow points to the deformed mitochondrion.)

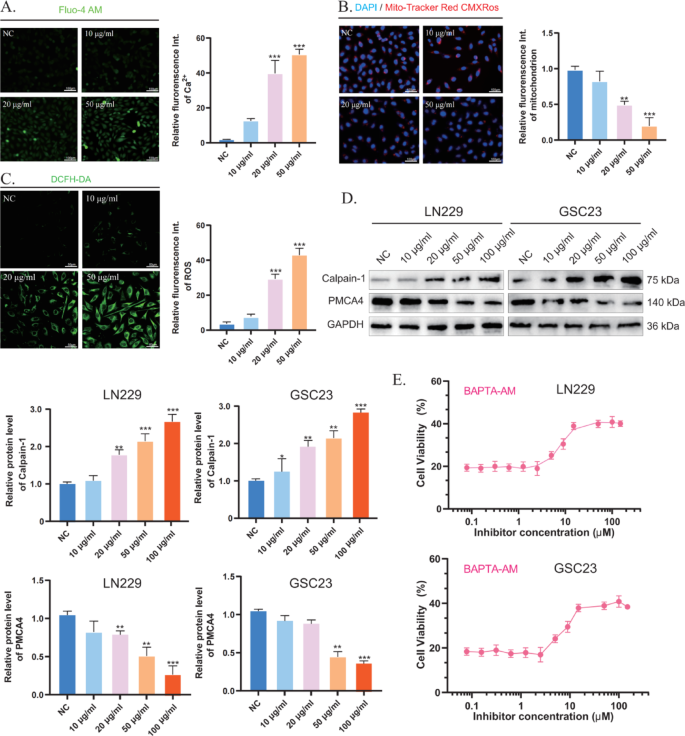

CaCN triggers intracellular calcium overload-induced apoptosis

As is well documented, Ca2+ plays a critical role in apoptosis [13]. The accumulation of Ca2+ in mitochondria leads to a sustained increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and ultimately to mitochondrial rupture and apoptosis. In general, when intracellular ROS levels are excessively high, they interact with proteins and trigger oxidative reactions that can alter protein structure and function [14]. Thus, in the presence of high levels of ROS, calcium channels, and pump proteins may undergo irreversible desensitization and damage [15]. The level of intracellular free Ca2+ following treatment with different concentrations of CaCN was detected using a Fluo-4 AM fluorescent probe (Fig. 5A), which can bind to Ca2+ to produce intense green fluorescence. As anticipated, the fluorescence intensity increased with increasing CaCN concentrations, indicating that CaCN increased intracellular Ca2+ levels. In addition, the MitoTracker Red CMXRos probe was employed to determine the degree of mitochondrial damage elicited by Ca2+ overload. Under physiological conditions (high mitochondrial membrane potential), MitoTracker Red CMXRos accumulates in the mitochondrial matrix and produces red fluorescence. Following mitochondrial damage (low mitochondrial membrane potential), the fluorescence intensity decreases (Fig. 5B) [16]. The results exposed that the fluorescence intensity decreased with increasing CaCN concentrations, indicating that CaCN-induced calcium overload strongly disrupted the mitochondrial membrane. The calcium pump PMCA4 ATPase is a calcium ion efflux pump present on the cell membrane and involved in the excretion of calcium ions from tumor cells, and its activity can be directly inhibited by ROS [15]. CaCN, owing to its peroxidase-like properties, catalyzes the generation of large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the tumor microenvironment of gliomas at low pH values. Thus, 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) was used to measure ROS levels in tumor cells, unveiling that ROS levels were significantly elevated in the CaCN group, thereby validating the peroxidase-like properties of CaCN (Fig. 5C). Afterward, Western blot analysis was conducted to detect the expression of calcium-related proteins in glioma cells in order to analyze the molecular mechanism of calcium overload. Calpain-1 is a calcium-regulated non-lysosomal thiol protease that can be activated by high concentrations of Ca2+ [17]. WB results showed that PMCA4 expression was down-regulated in glioma cells after CaCN treatment, whereas that of Calpain-1 was up-regulated. These results suggest that CaCN generates a large amount of ROS within the cells, and due to the ROS-mediated inhibition of calcium channels, the intracellular Ca2+ levels continuously rise, ultimately leading to calcium overload in glioma cells (Fig. 5D). Thereafter, the membrane-permeable Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM was used to determine the effect of Ca2+ overload on apoptosis. The survival rate of CaCN-treated glioma cells was significantly increased with gradient concentrations of BAPTA-AM, suggesting that CaCN-induced apoptosis was highly correlated with calcium overload (Fig. 5E).

CaCN, in contrast to conventional calcium-based nanomaterials, induces an increase in calcium ions while generating ROS through its POD-like enzyme properties, thereby inhibiting calcium channels and triggering calcium overload.

CaCN triggers intracellular calcium overload-induced apoptosis. A) Inverted fluorescence microscopy images of intracellular calcium ions in glioma cells after treatment with different concentrations of CaCN and corresponding semiquantitative analysis of intracellular calcium ion changes. (n = 3, mean ± SD, *p p p B) Mito-Tracker Red CMXRos staining of glioma cells after different treatments and corresponding Mito-Tracker Red CMXRos were analyzed semi-quantitatively for relative fluorescence intensity. (n = 3, mean ± SD, *p p p C) Detection of ROS in tumor cells treated with different concentrations of CaCN using 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA). D) Western blot analysis of calcium overload-related proteins (Calpain-1, PMCA4) in glioma cells after different treatments. E) Cell viabilities of glioma cells co-treated with CaCN and BAPTA-AM

CaCN triggers intracellular ferroptosis

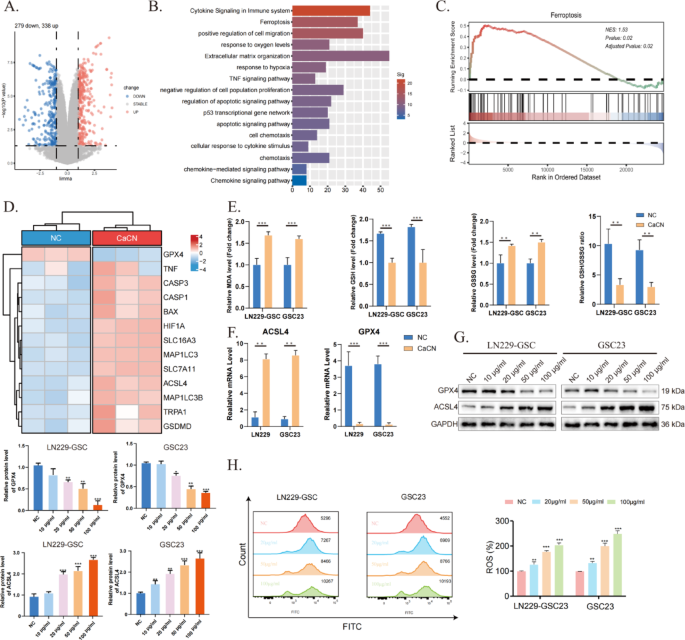

To identify genes involved in glioma cell death after CaCN treatment, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on three groups of normal GSC23 cells and three groups of CaCN-treated GSC23 cells. Volcano plots illustrate differences in gene expression in CaCN-treated glioma cells compared to the normal group (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, pathway enrichment analysis of up-regulated differential genes determined that death of CaCN-treated glioma cells was associated with pathways such as the immune pathway, apoptotic pathway, ferroptosis pathway, and sensitivity to hypoxia (Fig. 6B). Subsequently, the possible mechanisms of cell death were explored, and single-sample gene enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) highlighted that CaCN can induce ferroptosis (Fig. 6C). The heatmap illustrates differences in representative genes in the ferroptosis pathway (Fig. 6D).

Unlike other programmed cell death processes such as apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy, ferroptosis exhibits typical mitochondrial phenotypic changes, including mitochondrial shrinkage, membrane wrinkling, increased membrane density, and decreased mitochondrial cristae [18]. This is consistent with our observations under the transmission electron microscope. Ferroptosis is a novel type of iron-dependent programmed cell death characterized by lipid peroxidation and glutathione depletion [19]. In this study, the levels of GSH and MDA were determined in CaCN-treated glioma cells, observing that the levels of GSH/GSSG were decreased and the levels of MDA were increased, suggesting that CaCN induced the ferroptosis of glioma cells (Fig. 6E). Depletion of GSH inactivates GPX4 and induces lipid peroxidation, which in turn promotes ferroptosis. Therefore, the reduced expression of GPX4 is a key biomarker of ferroptosis [20]. In addition to GPX4, acyl-coenzyme A synthase long-chain member 4 (ACSL4) is another indicator of ferroptosis [21]. Consequently, the expression levels of GPX4 and ACSL4 were detected using PCR and WB. Reduced GPX4 expression and elevated ACSL4 expression levels were observed in the CaCN-treated group compared with the control group, implying that CaCN induced ferroptosis (Fig. 6F, G). Flow cytometry results further demonstrated increased ROS production in GBM cells after CaCN treatment (Fig. 6H).

CaCN triggers intracellular ferroptosis. (A) Differential gene volcano map of CaCN-treated GSC23 cells.(Log2Fold Change (FC) ≥ 1, Padj ≤ 0.05). (B) Pathway enrichment of up-regulated differential genes. (C) Related Pathways Enriched by ssGSEA. (D) Heat map of representative differential genes of related pathways.(Log2Fold Change (FC) ≥ 1, Padj ≤ 0.05). (E) Relative levels of MDA, GSH, GSSG, and the relative ratio of GSH/GSSG in CaCN-treated LN229 cells and GSC23 cells.(n = 3, mean ± SD, *p p p F) Relative mRNA levels of GPX4 and ACSL4 in CaCN-treated LN229 cells and GSC23 cells as determined by qt-PCR.(n = 3, mean ± SD, *p p p G) Western blot results of GPX4, ACSL4 and GAPDH in LN229 and GSC23 cells treated with different concentrations of CaCN. (H) Flow cytometry was performed to examine the changes in ROS in LN229 and GSC23 cells treated with different concentrations of CaCN

CaCN can remodel the tumor immune microenvironment

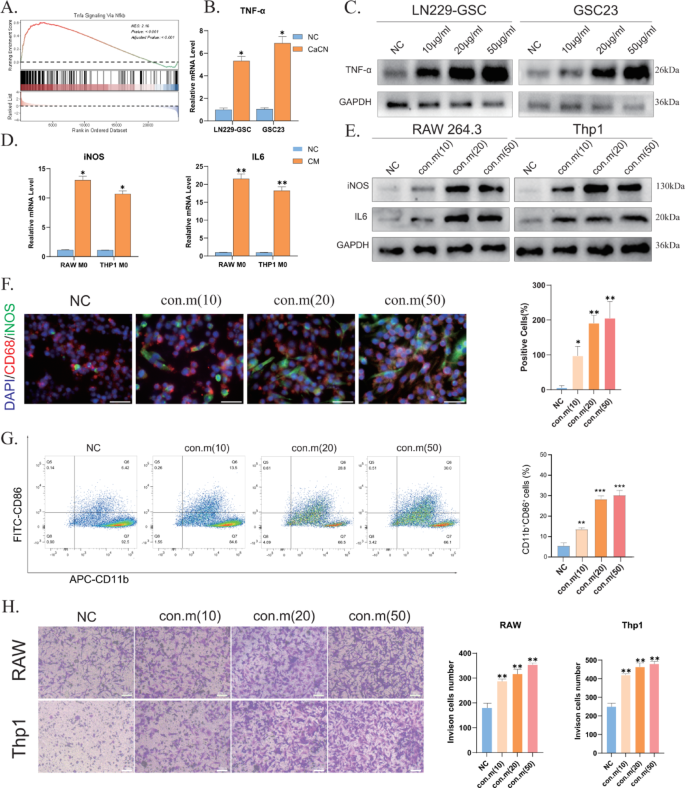

According to a previous study, inflammatory factors activate the Nfkb signaling pathway, stimulating tumor cells to synthesize TNF-α [22]. Pathway enrichment analysis revealed enrichment of immune-related pathways, including the TNF pathway (Fig. 5B). Performing ssGSEA on the differential genes identified via sequencing demonstrated enrichment of the TNF-α signaling pathway (Fig. 7A). At the same time, PCR and WB results indicated that CaCN drives TNF-α production in glioma cells (Fig. 7B, C), and the ability of glioma cells to synthesize TNF-α increased with increasing concentrations of CaCN. This effect may be ascribed to the release of associated inflammatory factors after lysosomal phagocytosis of CaCN.

TNF-α has been evinced to stimulate the polarization of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) from the M0 phenotype to the M1 phenotype [23], thereby reversing tumor immunosuppression. As a result, an increasing number of researchers are focusing on strategies to promote TAM polarization toward the M1 phenotype [24]. To determine the effect of CaCN on the immune microenvironment, the conditioned medium from GL261 and LN229 cells treated with CaCN was cultured with RAW264.7 and Thp1 cells (PMA-treated polarized to M0 macrophages). PCR and WB results revealed elevated expression levels of iNOS and IL-6 indicators in macrophages cultured in the conditioned media (Fig. 7D, E), suggesting macrophage polarization from the M0 to the M1 phenotype. To avoid the potential influence of CaCN itself on macrophages, we directly treated RAW and THP-1 cells with CaCN. PCR results showed that CaCN did not cause a significant increase in IL-6 and iNOS expression in macrophages, indicating that the direct effect of CaCN on stimulating macrophage polarization is limited (Supplementary Fig. 6 A). Additionally, the immunofluorescence (IF) assay suggested that as the concentration of CaCN increased, there was a more pronounced degree of polarization of macrophages cultured in the conditioned medium at the corresponding concentration (Fig. 7F), in line with the results of WB analysis. THP-1 macrophages induced to an M0 state with PMA were separately co-cultured with CaCN-treated glioma cell lines untreated with nanoscale enzymes for 36 h. Subsequent flow cytometry analysis revealed that macrophages demonstrated significant polarization towards an M1 phenotype following CaCN treatment (Fig. 7G). Following this, sequencing data and the cibersort algorithm were employed to analyze the immune infiltration of CaCN-treated glioma cells, which showed that CaCN-treated cells activated various immune cells, with elevated levels of M1 macrophages compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 5), corroborating our earlier findings.

In addition, chemokine-related pathways were also enriched (Fig. 6B). This suggests that in the presence of CaCN, glioma cells generate chemokines that potentially enhance macrophage chemotaxis and infiltration. Consequently, the Transwell co-culture system was used to assess macrophage chemotaxis and infiltration following M1 polarization. To simulate TEM, macrophages were cultured in the upper chamber, and a conditioned medium from glioma cells treated with different concentrations of CaCN was placed in the lower chamber. The Transwell co-culture system was employed to assess macrophage chemotaxis and infiltration following M1 polarization. Briefly, macrophages were cultured in the upper chamber, whereas a conditioned medium from glioma cells treated with different concentrations of CaCN was placed in the lower chamber. After 10 h of incubation, a progressive increase in the level of macrophage infiltration was noted with increasing concentrations of conditioned medium (Fig. 7H).

These results conjointly suggest that CaCN effectively induced TAM polarization toward the M1 phenotype, enhanced TAM infiltration, and exerted a multifaceted inhibitory killing effect on glioma cells.

CaCN can remodel the tumor immune microenvironment. A) Tnfa Signaling Via Nfkb Signaling Pathway Enriched by ssGSEA. B) Relative mRNA levels of TNF-αin CaCN-treated LN229 cells and GSC23 cells as determined by qt-PCR.(n = 3, mean ± SD, *p p p C) Western blot results of TNF-α and GAPDH in LN229 and GSC23 cells treated with different concentrations of CaCN. D) Relative mRNA levels of iNOS and IL6 in condition media-treated RAW264.7 cells and Thp1 cells as determined by qt-PCR.(n = 3, mean ± SD, *p p p E) Western blot results of iNOS and IL6 in RAW264.7 cells and Thp1 cells treated with different conditioned media. F) Detection of iNOS expression in RAW264.7 cells using immunofluorescence staining after 6 h of culture in conditioned medium of GL-261 cells treated with different concentrations of CaCN. (saclebars,100 μm)Percentage of iNOS-expressing positive cells in RAW264.7 cells treated with different conditioned media counted using image J counting.(n = 3, mean ± SD, *p p p G) Flow cytometry was performed to examine the proportion of M0-type THP1 cells polarised to M1-type macrophages after treatment with different concentrations of conditioned medium. H) The infiltration of RAW264.7 cells and Thp1 cells that have been induced to M1 morphology in the transwell system were treated with different concentrations of conditioned medium, respectively. The number of invaded cells after transwell of RAW264.7 and Thp1 cells treated with different concentrations of conditioned medium was obtained using image J counting.(n = 3, mean ± SD, *p p p

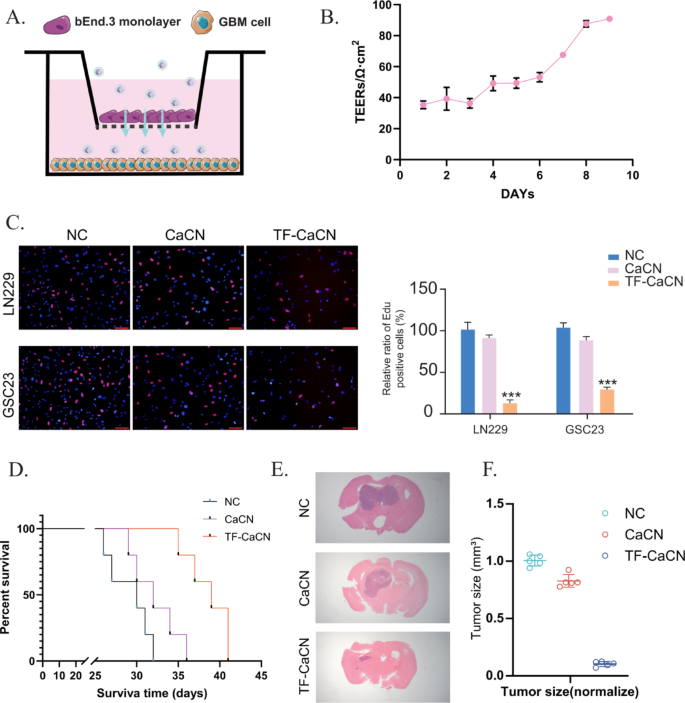

TF-CaCN effectively enhanced the permeability of the blood-brain barrier

Although single-atom nanozymes can penetrate the blood-brain barrier to some extent, their penetration efficiency is relatively low. Therefore, we introduced transferrin (TF) to enhance the targeting and penetration efficiency of CaCN across the blood-brain barrier, thereby improving its potential for clinical application.

First, characterization analysis showed the average hydrodynamic diameter of TF-CaCN (Supplementary Fig. 6B), confirming the successful modification with TF and indicating that the size distribution was within the expected range. In the TEM images (Fig. 4E), TF-CaCN displayed lipid-like coating surrounding the dense CaCN core, indicative of PEG encapsulation. These vesicular features were observed before complete lysosomal digestion, consistent with partial lipid coverage. Then we verified in vitro whether the addition of the TF ligand in TF-CaCN would alter the original catalytic efficiency. CCK8 results showed that the IC50 values of TF-CaCN and CaCN were very similar (Supplementary Fig. 6 C). On the other hand, WB results indicated that TF-CaCN, like CaCN, can modulate the activity of calcium ion channel proteins (Supplementary Fig. 6D). The results indicate that the TF ligand does not alter the inherent properties of CaCN.

To evaluate BBB penetration in vitro, we established a Transwell BBB model using bEnd.3 endothelial cells (Fig. 8A). Briefly, 1 × 10^6 bEnd.3 cells were seeded onto 2% gelatin–precoated inserts and cultured with medium changes every 3–4 days until barrier formation, as indicated by transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER). When TEER reached approximately 100 Ω·cm², the BBB was considered successfully established (Fig. 8B). GBM cells were cultured in the lower chamber, while CaCN or TF-CaCN was added to the upper (endothelial) side of the insert to mimic luminal exposure.

The EdU assay revealed clear differences in nanoparticle penetration. Compared with CaCN, TF-CaCN treatment resulted in markedly reduced EdU incorporation in GBM cells in the lower chamber (Fig. 8C). This indicates that TF-CaCN crossed the endothelial monolayer more efficiently, delivering higher amounts of active nanozymes to the glioma cells beneath the barrier. Thus, the in vitro results provide direct evidence that transferrin modification greatly enhances BBB permeability and subsequent antitumor effects.

We further validated these findings in vivo using an intracranial orthotopic glioblastoma model. After tumor implantation, mice were treated by tail vein injection with either CaCN or TF-CaCN. Survival analysis demonstrated that mice receiving TF-CaCN survived significantly longer compared with those treated with CaCN (Fig. 8D). In addition, H&E staining of brain sections revealed smaller tumor volumes and reduced tumor cell density in the TF-CaCN group (Fig. 8E–F). These in vivo results confirm that transferrin conjugation improves the systemic delivery of CaCN across the BBB and enhances accumulation at tumor sites.

Taken together, both the in vitro BBB model and the in vivo glioma model consistently demonstrate that transferrin modification significantly improves the BBB penetration ability of CaCN. This provides strong support for the use of TF-CaCN as a clinically translatable nanosystem capable of achieving effective and targeted delivery to glioblastoma tissue.

TF-CaCN effectively enhanced the permeability of the blood-brain barrier. A) Schematic diagram of the in vitro BBB model. B) After establishing the in vitro BBB model, TEER values were measured daily. C) EDU assay results indicated that TF-CaCN effectively penetrated the BBB model and inhibited GBM cell proliferation, whereas CaCN exhibited significantly lower penetration efficiency. D) Survival curves of each group of mice following treatment with CaCN and TF-CaCN, respectively. E) H&E staining of intracranial tumors from each group of mice after treatment with CaCN and TF-CaCN, respectively. F) Tumor volume statistics of intracranial gliomas in each group of mice after treatment with CaCN and TF-CaCN, respectively

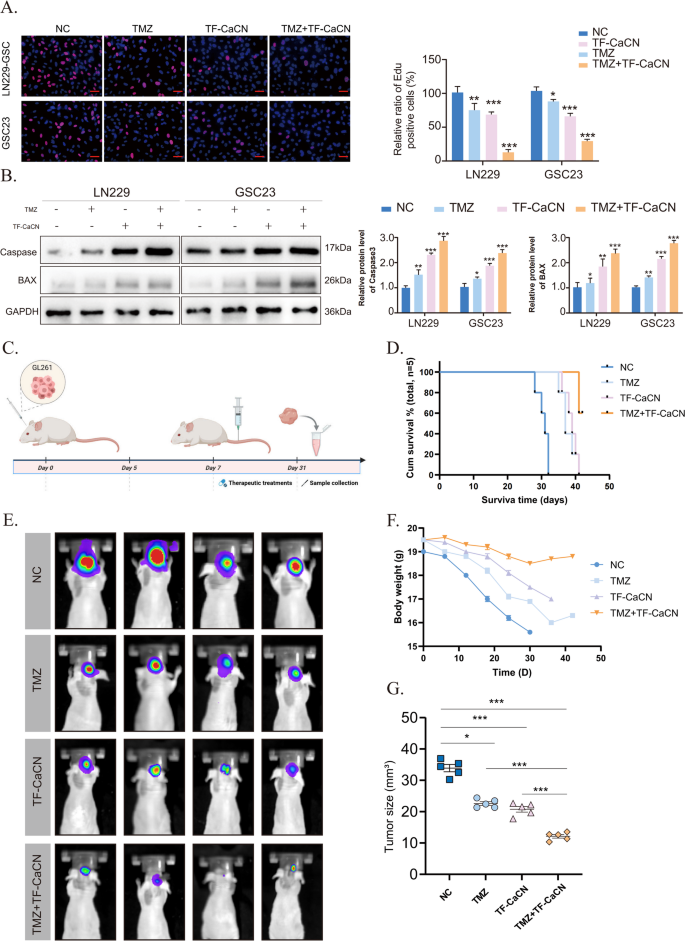

CaCN enhances the efficacy of temozolomide and inhibits tumor proliferation in vivo

Temozolomide (TMZ) is a commonly used chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of glioma and is considered the most effective therapeutic agent for glioma owing to its oral administration, ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier, stability in acidic environments, and low toxicity profile [25]. Despite its combination with other drugs substantially improving the survival outcomes of patients after surgical intervention, the efficacy of TMZ remains sub-optimal in clinical practice [26]. Of note, glioma resistance to TMZ is the primary cause of chemotherapy failure [27]. Considering that several studies have highlighted the crucial role of ferroptosis in conferring drug resistance [28], we posit that the combination of CaCN and TMZ may enhance the killing of tumor cells.

The EDU results showed that the combination treatment of TMZ and TF-CaCN inhibited GBM cell proliferation more effectively than either treatment alone (Fig. 9A). Indeed, WB results showed that the apoptotic effect was significantly enhanced by the co-administration of TMZ and CaCN (Fig. 9B), suggesting that CaCN may synergistically enhance the efficacy of TMZ.

Subsequently, we conducted in vivo drug treatment experiments (Fig. 9C). Starting on day 7 post-tumor implantation, when intracranial tumor growth was established, mice received PBS, TMZ, TF-CaCN, or TMZ + TF-CaCN intravenously every other day at a dose of 1 mg/kg for 2 weeks. Mice in different groups received intravenous injections of TMZ, TF-CaCN, or a combination of both. Survival analysis and body weight measurements indicated that the combination therapy significantly improved the prognosis of glioblastoma-bearing mice compared to monotherapies (Fig. 9D, F). In vivo fluorescence imaging further demonstrated that the combined treatment effectively suppressed tumor growth (Fig. 9E, G). These findings strongly support that TF-CaCN enhances the therapeutic efficacy of TMZ. Importantly, IHC results demonstrated that CaCN activated peritumoral CD4 and CD8 indicators, indicating that the immune system was activated and altered the immune microenvironment in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 7). In addition, Hematoxylin Eosin (H&E) staining of major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys) harvested from treated mice showed no significant histopathological damage in the TF-CaCN-treated group (Supplementary Fig. 8). Overall, these results indicated that CaCN nanozymes possessed satisfactory tumor growth inhibitory activity in vivo.

TF-CaCN enhances the efficacy of temozolomide and inhibits tumor growth in vivo. (A) The EDU results demonstrated that the combination of TMZ and TF-CaCN effectively inhibited the proliferation of GBM cells in in vitro experiments. (B) Western blot results of caspase3, BAX, and GAPDH in IC50 concentrations of TF-CaCN, TMZ, and TMZ + TF-CaCN-treated LN229 and GSC23 cells. (C) Flowchart of drug administration after in situ modelling of intracranial gliomas in mice. (D) Survival of model mice after treatment with TMZ, TF-CaCN and drug combination, respectively. (E) Animal in vivo fluorescence imaging results showing intracranial tumour volumes in model mice of different treatment groups. (F) Body weight changes in model mice after treatment with TMZ, TF-CaCN and drug combination, respectively. (G) Comparison of tumour size in different treatment groups