Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

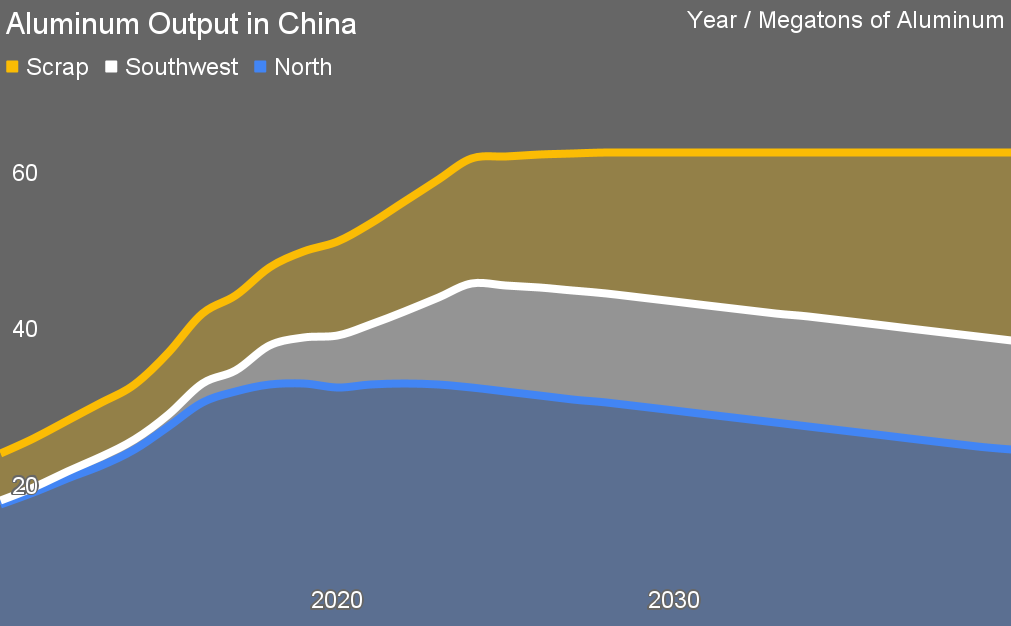

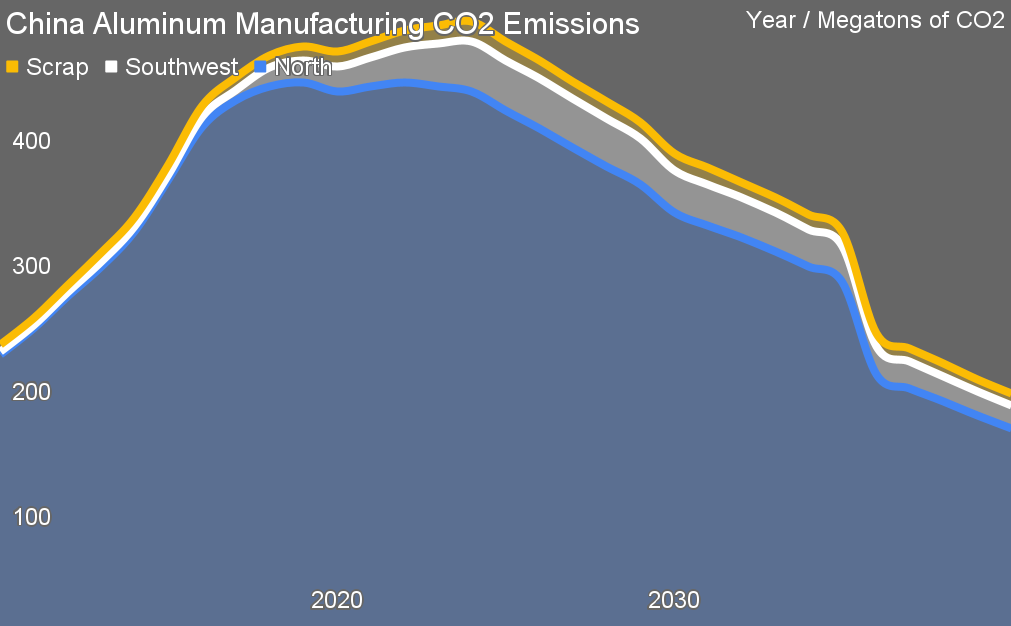

China’s aluminum manufacturing CO2 emissions likely peaked in 2024, not because production collapsed or because a single policy suddenly bit, but because the structure of where aluminum is made and how it is made changed in ways that compound over time. Aluminum is a useful material to examine because it is dominated by electricity demand, geographically sensitive, and produced at a scale where relatively small structural shifts show up clearly in national emissions data.

China now produces about 44 million tons of primary aluminum per year, close to 60% of global output. Producing one ton of primary aluminum requires roughly 13 to 15 MWh of electricity, depending on potline design and operating conditions. In coal dominated grids common in northern China a decade ago, electricity alone added around 9 to 14 tons of CO2 per ton of aluminum, before accounting for another 1.5 to 2 tons from carbon anodes. At scale, this made aluminum one of China’s most emissions intensive industrial activities, with total sector emissions easily exceeding 400 million tons of CO2 per year.

From the early 2000s through about 2014, aluminum production expanded rapidly in coal heavy provinces such as Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Henan, Shandong, and Xinjiang. The logic was straightforward. Coal was abundant, power prices were low, and provincial governments welcomed large industrial loads that justified power plant construction and generated fiscal revenue. Environmental constraints existed but were secondary. During this period, primary aluminum output rose almost in lockstep with coal generation, and sector emissions climbed accordingly.

That pattern began to change in the mid 2010s. Air pollution pressures intensified, coal overcapacity became politically sensitive, and large hydro projects in southwestern China reached completion. Provinces such as Yunnan and Sichuan suddenly had large volumes of low marginal cost electricity with limited local demand. Aluminum smelting, which operates continuously and values long term power contracts, became an obvious anchor load for this electricity. Beginning around 2014 to 2015, China initiated a large scale geographic reallocation of aluminum smelting.

This reallocation was not incremental retrofitting. Some smelters were shut down in coal regions and many more new facilities were built in hydro rich provinces, often separated by distances of 1,000 to more than 2,500 km. Potlines, foundations, and busbar systems were scrapped rather than moved. New facilities were designed around higher amperage standards and local power conditions. By 2023 to 2024, roughly 13 million tons per year of China’s primary aluminum production capacity, and most years of actual output, was located in hydro dominated provinces, compared to roughly 1 to 2 million tons a decade earlier.

The emissions impact of this shift was immediate and large. Hydro based smelting typically carries electricity emissions closer to 0.3 to 1.5 tons of CO2 per ton of aluminum, depending on dry season fossil backup. Even holding anode emissions constant, relocating 13 million tons of output from coal dominated grids reduced emissions by roughly 8 to 11 tons of CO2 per ton of aluminum. That implies annual savings on the order of 100 to 140 million tons of CO2, comparable to the total emissions of a mid sized industrial economy.

At the same time, Beijing formalized a national primary aluminum capacity cap of roughly 45 million tons in 2017. This cap did not immediately freeze production levels. It constrained where growth could occur. Actual primary aluminum output continued to rise for several years after the cap was introduced, driven by improved utilization of modern potlines, replacement of illegal or sub scale capacity, and relocation to hydro regions. By 2024, actual output reached about 43.8 million tons, close to the nominal ceiling.

Looking at actual output rather than installed capacity clarifies an important point. Coal heavy primary aluminum output did not collapse when the cap was introduced. It continued rising through the late 2010s, peaking around 2018 to 2020 at roughly 31 million tons per year. After that point, coal region output flattened and then began a slow decline. All net growth in primary aluminum after 2020 came from hydro dominated provinces.

This distinction matters for understanding emissions dynamics. Total primary aluminum output continued to grow into the early 2020s, but the dirtiest tranche of that output stopped growing several years earlier. Once coal heavy aluminum production plateaued, every additional ton of aluminum produced nationally came with a much lower carbon footprint than the tons added before it.

A second structural shift was occurring in parallel. China’s recycled or secondary aluminum output rose from around 6 million tons per year in the early 2010s to about 11 million tons per year by 2023 to 2024. Secondary aluminum requires only about 0.7 to 1.0 MWh of electricity per ton, roughly 5 to 10% of the electricity required for primary production. Typical emissions fall in the range of 0.5 to 1.5 tons of CO2 per ton, depending on electricity source and scrap quality.

The rise in secondary aluminum reflects the maturation of China’s material stock. Buildings, vehicles, appliances, and infrastructure built during the 1990s and 2000s are now reaching end of life, releasing large volumes of scrap. Industrial scrap from manufacturing continues to grow as well. Recycling economics are strong even without climate policy, because electricity costs dominate aluminum economics and recycled material avoids that burden.

A common intuition is that as China’s infrastructure buildout enters its end phase, aluminum demand should fall sharply. Construction related demand has indeed peaked, particularly for bulk extrusions tied to new floor space. However, total aluminum demand has not collapsed. Instead, it has flattened and in some years continued to grow modestly. Aluminum has increasingly become a technology and manufacturing material rather than a pure construction input.

Electric vehicles use more aluminum per vehicle than internal combustion models, particularly in body structures, battery enclosures, and thermal systems. China produces tens of millions of vehicles annually, so even incremental increases in aluminum intensity add up to several million tons of demand. Power systems absorb aluminum in solar frames, wind components, inverters, substations, and storage systems. Export oriented manufacturing embeds aluminum that leaves the country indirectly, even when primary aluminum exports are restricted. These segments do not replace the construction boom of the past, but they are large enough to support a plateau.

As secondary aluminum output rises and total demand flattens, primary aluminum must eventually decline in absolute terms. The mass balance is unavoidable. In practice, the decline is delayed by alloy constraints, blending requirements, and export demand, which allow primary aluminum to remain in the system longer even as recycling expands. The result is a gradual transition rather than a sharp drop.

When primary aluminum does decline, the reductions occur overwhelmingly in coal heavy regions. These smelters sit at the top of the cost and emissions stack. Hydro based smelters in Yunnan and Sichuan are politically framed as anchors for clean electricity and are protected accordingly. Closing coal based smelters improves local air quality, reduces coal plant utilization, and aligns with national climate objectives. Incremental reductions of 1 to 2 million tons per year in coal regions are easier to absorb than equivalent cuts elsewhere.

An important correction is that coal heavy regions are not standing still electrically. Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, and Xinjiang are now among China’s largest wind and solar buildout zones, paired with storage and ultra high voltage transmission. Aluminum smelters increasingly contract power that includes large renewable shares with coal firming rather than pure coal supply. As a result, the carbon intensity of aluminum produced in these regions is likely to fall substantially over the next 15 years even if coal remains part of the mix.

A reasonable median trajectory is that coal region primary aluminum intensity falls from roughly 12 to 14 tons of CO2 per ton today to around 9 to 11 tons by 2030 and 6 to 8 tons by 2040. Hydro region aluminum, already much cleaner, may fall from around 2 to 3 tons of CO2 per ton today to about 1 to 1.5 tons by 2040. Secondary aluminum, already near the floor, may decline from roughly 0.6 to 1.2 tons today to around 0.2 to 0.5 tons as electricity continues to decarbonize.

These shifts explain how aluminum manufacturing emissions can peak without a collapse in output. Coal region aluminum output stops growing first. Hydro region output grows at much lower intensity. Secondary aluminum displaces primary at the margin. At the same time, the carbon intensity of remaining coal region aluminum declines. No single lever dominates. The emissions peak emerges from the interaction of all four effects.

In practical terms, the system ran out of upward emissions drivers before it ran out of aluminum demand. In 2014, nearly every incremental ton of aluminum added roughly 10 to 12 tons of CO2. By 2024, incremental aluminum added closer to 1 to 3 tons of CO2, and in some years added little or none on a net basis. That arithmetic shift is the core reason emissions flatten and then turn down even as output remains high.

Taken together, these dynamics make 2024 a plausible peak year for China’s aluminum manufacturing emissions. Relocation to hydro regions is largely complete. Secondary aluminum is rising into double digit millions of tons. Coal heavy output has already peaked and begun to edge down. Renewable penetration in coal regions continues to rise. Reversing this trend would require renewed growth in coal based smelting or a collapse in recycling, neither of which fits China’s industrial or energy trajectory.

Aluminum offers a preview of how industrial decarbonization unfolds in a mature, electricity dominated material system. Emissions peak before output does. Geography matters more than incremental process tweaks. Recycling becomes the growth engine. Decline is gradual and managed rather than abrupt. In China’s case, aluminum is likely to be one of the first major industrial materials where this pattern is clearly visible in the data, not because it was easy, but because the underlying math finally stopped pointing upward.

Support CleanTechnica via Kickstarter

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy