Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

Canada has just shifted its electric vehicle policy architecture. Instead of relying on an explicit EV sales mandate, the federal government has moved toward tightening fleet average emissions standards combined with credit trading and trade policy adjustments. On the surface, this looks like a procedural change. In practice, it changes how compliance is calculated, how money moves between firms, and how quickly automakers must adjust their product mix.

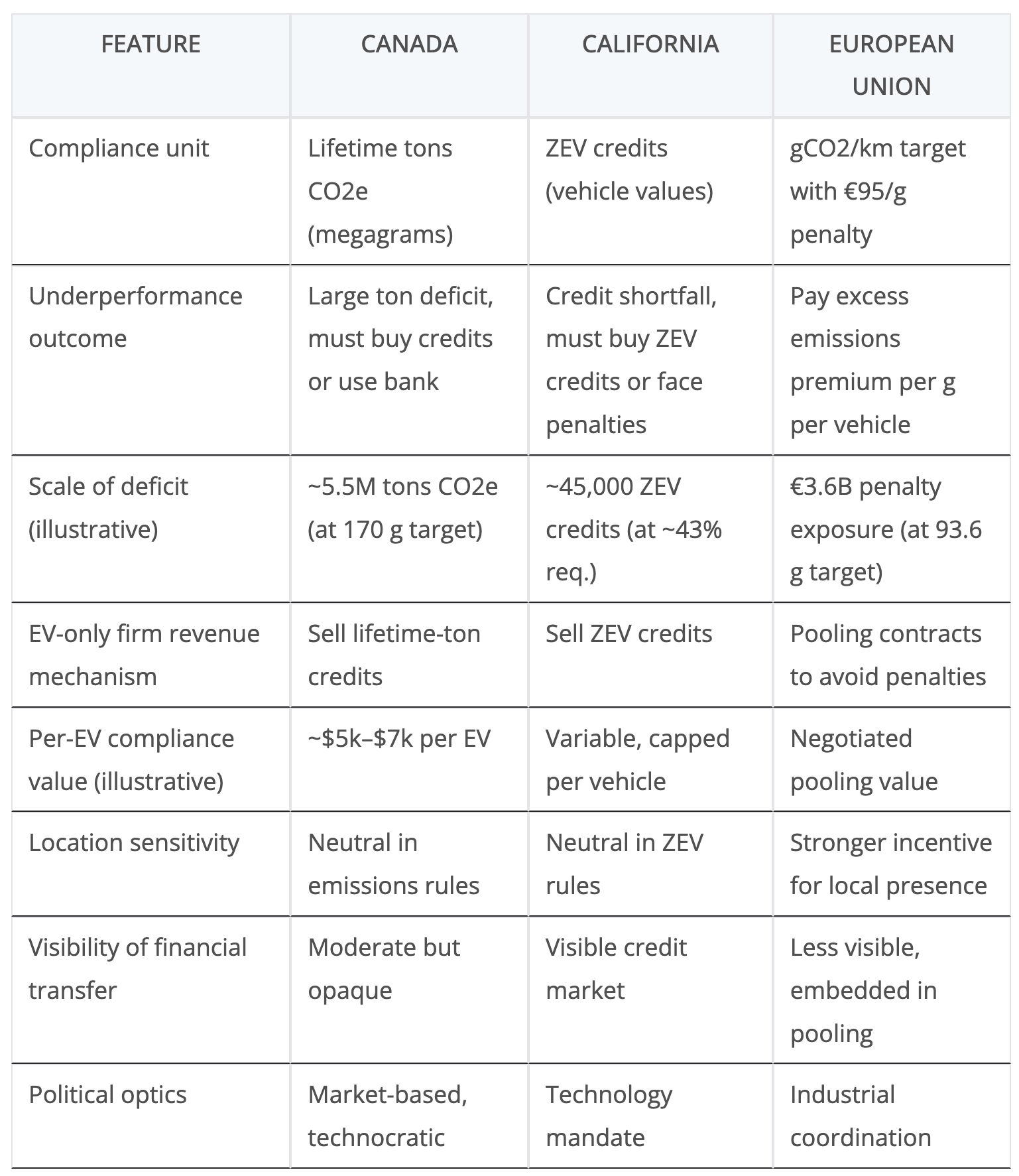

To understand what this means, it helps to compare Canada’s approach with two other major regulatory systems: California’s ZEV credit program and the European Union’s fleet average CO2 standards with penalty backstops and pooling. All three are designed to reduce tailpipe emissions from new vehicles. All three push automakers toward higher EV penetration. But they do so using different compliance units, different market structures, and different financial pathways. The differences are not academic. They shape competitive dynamics and capital flows in ways that matter for both incumbents and new entrants. For details on the Canadian system and its implications, please see my previous assessment explicitly of the new approach.

Take a single hypothetical automaker selling 300,000 vehicles per year into each major market. Assume 8% of those sales are battery electric vehicles and the remaining 92% are internal combustion pickups and SUVs averaging roughly 240 gCO2 per km. That yields a blended fleet average of about 221 gCO2 per km. Now place that same company into the three different regulatory systems. Ignore the real variance in vehicle sizes and emissions between European and North American fleets for the purposes of this analysis. The underlying emissions problem is identical, but the financial consequences are not. The differences are not cosmetic. They shape capital flows, competitive advantage, and industrial strategy.

Canada’s light duty greenhouse gas regulations are built around a fleet average CO2 standard expressed in grams per mile, converted into credits and deficits measured in lifetime tons of CO2. The regulation sets a target A, compares it to the manufacturer’s achieved fleet value B, multiplies the difference by vehicle count and an assumed lifetime mileage, and converts the result into megagrams of CO2. Environment and Climate Change Canada’s regulations specify lifetime mileage assumptions of roughly 195,000 miles for passenger automobiles and about 226,000 miles for light trucks. The compliance unit is not a vehicle or a percentage. It is mass.

Apply that structure to the hypothetical automaker in a year where the effective fleet target is 170 gCO2 per km. The achieved fleet average is about 221 gCO2 per km, leaving a gap of 51 g per km. Convert to grams per mile and apply the light truck lifetime mileage assumption. The deficit works out to roughly 18.5 tons of CO2 per vehicle. Across 300,000 vehicles, that is about 5.5 million tons of lifetime CO2 deficit. Those tons can be covered by banked credits or purchased from other manufacturers. They are tradable, and they accumulate quickly because the compliance unit reflects decades of expected driving.

That structure has two material effects. First, per vehicle credit quantities are large. A single zero emission SUV sold into a 170 g per km standard can generate on the order of 60 tons of lifetime credits. Second, the financial transfer between high emitting and low emitting fleets can reach hundreds of millions of dollars at modest credit prices. If credits clear at $100 per ton, 5.5 million tons represents $550 million of exposure for the hypothetical automaker. Canada’s system therefore behaves like a commodity market in carbon mass, even though it is embedded inside a vehicle rule.

California’s Advanced Clean Cars and ZEV framework operates differently. The compliance unit is not tons of CO2 but ZEV credits tied to vehicle characteristics, including electric range. The regulations allocate credits per qualifying vehicle, often calculated from range using formulas such as 0.01 times the UDDS range plus 0.50, with caps that limit per vehicle credits. A 300 mile battery electric vehicle earns around 3.5 credits under commonly cited formulations. Compliance obligations are expressed as a percentage of sales that must be covered by ZEV credits. Reuters and regulatory analyses have referenced requirements in the 40% range in the late 2020s.

Apply that to the same 300,000 vehicle automaker in a year with a 43% ZEV requirement. The firm would need 129,000 ZEV credits. At 8% EV share and 3.5 credits per EV, it would generate about 84,000 credits, leaving a shortfall of 45,000 credits. The compliance gap is expressed in vehicle credit units, not tons. The magnitude feels smaller in raw numbers, but the economics depend on the credit price. California has an explicit trading mechanism. Credit values fluctuate based on supply and demand, but per vehicle credit generation is capped by design. That limits how much compliance value an individual EV can produce.

The European Union takes a third approach. The EU sets fleet average CO2 targets in grams per km and imposes an excess emissions premium of €95 per g per km per vehicle of exceedance. For 2025 to 2029, the car target is 93.6 gCO2 per km. If the hypothetical automaker’s fleet average were 221 g per km against a 93.6 g target, the exceedance would be about 127 g per km. Multiply by €95 and by 300,000 vehicles and the theoretical exposure approaches €3.6 billion. That number is not intended to be paid. It exists as a backstop to drive compliance.

The EU provides flexibility through pooling arrangements. Manufacturers can form pools and comply jointly, which redistributes compliance burdens contractually rather than through a standardized credit commodity. There is no open market in lifetime tons of CO2 or capped vehicle credit tiles. There is a penalty anchored in regulation and a negotiated path to avoid it. The compliance unit is simple. The financial consequence is transparent. The monetization pathway is relational.

Comparing the compliance units clarifies the structural differences. Canada monetizes lifetime carbon mass. California monetizes ZEV vehicle credits. The EU monetizes exceedance through a fixed per gram penalty. In Canada, credit quantities per EV are large because they embed lifetime mileage assumptions. In California, credit quantities per EV are bounded by range based formulas and caps. In the EU, there is no standardized credit commodity. The backstop is a fine, and the main flexibility is pooling.

These differences shape where money flows. In Canada, an EV only firm selling into a tightening standard can generate tens of tons of credits per vehicle. At $80 to $120 per ton, that can translate into $5,000 to $7,000 per vehicle in compliance value. Multiply by tens of thousands of vehicles and the numbers are large. In California, the same firm generates credits in units of 3 to 4 per vehicle. The financial outcome depends on the credit price, but the system constrains per vehicle monetization through caps. In the EU, value is captured through pooling negotiations rather than open credit trades.

Industrial implications follow from these mechanics. Canada’s system is location neutral within the emissions rule. Credits accrue to the regulated entity that sells the vehicle, whether built domestically or imported. That can make credit generation a meaningful revenue stream for EV only importers. California is also location neutral within the ZEV rule. The incentive to localize production there comes from federal tax credits and trade policy rather than the ZEV math itself. The EU operates inside a broader industrial policy context. Pooling, state aid rules, battery regulations, and trade measures intersect with the CO2 framework, creating stronger incentives for firms to embed production locally.

Political optics differ as well. Canada’s model looks technocratic and market based. The compliance unit is carbon mass and credits trade between firms. California’s model is visibly a deployment requirement expressed in percentage terms. The EU’s model is anchored in a clear penalty that is easy to explain. All three push manufacturers toward electrification. The pace and financial texture differ.

For the hypothetical automaker, the direction of travel is similar in all three systems. At 8% EV share and a truck heavy mix, compliance gaps are large. In Canada, the gap is measured in millions of tons of lifetime CO2. In California, it is measured in tens of thousands of ZEV credits. In the EU, it is measured in billions of euros of theoretical penalty exposure. The arithmetic forces a shift in sales mix regardless of the jurisdiction. The difference lies in how that shift is financed, who captures transitional rents, and how transparent the cost signal appears to executives and investors.

The material conclusion is that regulatory design shapes capital flows as much as stringency shapes emissions outcomes. Canada’s lifetime ton credit structure creates large visible compliance commodities. California’s ZEV credit system creates a bounded but liquid vehicle credit market. The EU’s penalty and pooling structure embeds compliance inside coordinated industrial arrangements. Automakers planning for the next decade need to understand not only how tight targets will be, but how those targets are translated into financial obligations. The compliance unit matters. The shape of the market matters. And in each jurisdiction, the arithmetic leaves little room for standing still.

Support CleanTechnica via Kickstarter

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy